Benghazi internal security headquarters, November 3, 1990. A fax arrives at 10:30 in the morning, addressed to the director from the head office in Tripoli.

"We received information about some of the suspicious people," it begins. A list of names and paragraphs of information follow.

One man is singled out for listening to religious tape cassettes from an Egyptian sheikh. Another man named Bileid is identified as a teacher and a "big criminal," someone who has grown a beard.

At the bottom of the page is Eissa Ahmed al-Farsi. He was fired from his job as an agricultural studies teacher at Omar Mukhtar University in Baida. He belonged to one of Libya’s secretive revolutionary committees, the power behind Muammar Gaddafi’s regime, but dropped out. He began spending time with bearded men at the Abu Bakr al-Siddiq mosque in Benghazi.

The fax is stamped and dated. "Peace," it says at the end.

Farsi's large, blue surveillance file is number 6,247. At the bottom, it is marked "very secret." He is one among tens of thousands, each for a Libyan who unwittingly became a target of Gaddafi’s secret police, the enforcers responsible for squashing dissent and sowing terror over more than four decades in the Libyan Arab People’s Jamahiriya.

In theory, the Jamahiriya – or "state of the masses" – is run by people’s committees and an enormous, directly elected congress, but in practice, Gaddafi’s personally loyal, autocratic, and extra-judicial state apparatus is controlled through community-based revolutionary committees, the lijan thawriya. High-ranking army, police and internal security officers often double as committee members. For decades, they have had the ability to arrest, interrogate, torture and imprison Libyan citizens at will.

Now that Gaddafi's regime has fallen in the east, stories like Farsi's – detailing the government's far-reaching coercive power – are finally entering public view.

'Heresy'

Farsi’s file was only one among stacks of thousands stored in an internal security office on Benghazi’s Mediterranean waterfront, next to the main courthouse that has since been converted into the opposition’s political headquarters.

One day in late February, during the chaotic and bloody beginning of the uprising against Gaddafi, the building began to burn. Benghazi had become a warzone, and security officers and army troops were gunning down protesters in the street. On the day the building burned, security forces had left the office to respond to a mob that was trying to break into the city’s main security directorate, a few miles away.

A group of residents rushed to the burning building and broke down one of its locked doors. Among them was 36-year-old Awad Gheriani. As Gheriani’s group entered, he saw employees rush outside through another door. Gheriani assumed the fire had been ignited intentionally by security officials hoping to hide their work. Already, the blaze had destroyed rooms and made parts of the building impossible to reach. Gheriani and the others grabbed whatever they could and ran out. Among the pile under his arm was Farsi’s file.

The file’s 22 pages, containing a decades-long correspondence between various arms of the country’s security forces, points to the regime’s deep fear of the slightest opposition to Gaddafi’s rule, particularly from religious sources.

Because Farsi began attending the Abu Bakr al-Siddiq mosque and associating with bearded men, his case attracted the attention of a special agency aimed at combating “zindaka,” a word that translates literally as “heresy” but came to mean, under four decades of Gaddafi’s rule, those who disagreed with his unique vision of the Jamahiriya, a society in perpetual revolution.

Over 18 years, the internal security forces kept a constant eye on Farsi, instructing various arms of the government to provide information about him.

After leaving Omar Mukhtar, Farsi was hired as an economics lecturer at Gar Younis University in Benghazi. In 2007, the internal security forces sent a letter to the university ordering them to provide information on Farsi. The same year, the agency in charge of issuing passports and monitoring travel reported to internal security that they had no information about Farsi, aside from an order to detain him.

In 2008, Benghazi’s internal security director, Brigadier General Senussi al-Wizri – who since has been jailed by the opposition – wrote to the anti-heresy agency that while Farsi displayed signs of “zindaka,” he had “good character”. Wizri concludes by updating the agency on Farsi’s address, and the file comes to an end.

'Sleeper cells'

Ayman Gheriani, Awad’s brother, worked as a criminal prosecutor in Benghazi for years, but he was never allowed to see something like Farsi’s file. His caseload was limited to street fights, robberies and murders.

The work of the internal security forces and the testimony given to revolutionary committees by their enormous web of informants was never subject to legal review, Gheriani said.

“Being able to see top secret stuff means being able to carry out your orders without any judicial process,” he said. “They name their own instructions, they don’t have to take it to a judge.”

Civilians could be detained without so much as a pretext and referred to special revolutionary courts – or no courts at all. Attempting to form a political party or joining an Islamic group were known as easy ways to provoke the security forces into action.

Once inside the system, one’s fate became arbitrary.

“It’s not like there’s protocol. The person asking questions has ultimate decision-making power,” Gheriani said.

Sometimes, the suspicions of a neighbor were all it took.

Bilgassim al-Shibani’s file, number 6,248, came after Farsi’s in the stack. It opens in 2007, with a letter to the internal security forces from a man who lived in Shibani’s apartment building in central Benghazi.

Shibani is a single man, the informant writes, and he sometimes hosts a group of four to six bearded young men – none of them older than 25 – on the building’s rooftop after midnight. The group arrives in a gold-colored BMW 520 with a foreign license plate, he explains.

Shibani’s file is only a few pages long, but it ends with a letter from Wizri’s office directing local police detectives to follow and observe Shibani. Break into his apartment if necessary, it says.

There was never a guarantee the security forces would vet the informant. The man may only have had a quarrel with Shibani and could have been fabricating the story, Gheriani pointed out. Helping the revolutionary committees identify suspected dissidents was a dependable way to get ahead in Libya, no matter one’s profession.

“It’s like a gang, a mafia, if you’re an honest person you get nothing,” Gheriani said.

Among the files recovered from the internal security building were applications to the revolutionary committees from Benghazi residents. In addition to sections for name, address, and birthplace, there were those for weapons training and expertise.

Many residents believe former revolutionary committee members have organized “sleeper cells” in the wake of the uprising to sabotage rebel military bases and launch sudden attacks. When Gaddafi’s forces began their bombardment of Benghazi on March 19 and approached the southern outskirts of the city before being driven off by foreign air strikes, gunmen in plain clothes fought street battles with revolution forces in the city and staged drive-by shootings on residents preparing its defenses.

Gheriani estimates that around 200 ex-committee members remain in Benghazi. Some are in hiding, and others have fled.

'Oppressed people'

The lijan thawriya may be dispersed in the east, but their shadow will remain for many years. Tens of thousands of people have been spied upon by a network of informers that included friends and neighbors. Families have seen fathers and brothers disappear into Libya’s prison system for decades. Many were never to be heard from again.

Compared to some, 51-year-old Abdelmoneim Belruin is lucky: He spent just seven years in custody.

Belruin made the mistake of maintaining friendships with a group of men who founded a community service organization in Benghazi, the “Honorable Patriots”. The group met for coffee one day in 1981 on Rayid Street; as they left, they were swarmed by cars and arrested. Belruin would later find out that Idris Bourwas, an army officer he once met in one of his friend’s living rooms, had double crossed them.

The men were taken to an Interior Ministry building in Benghazi. Wizri, the internal security chief, was present. Officers stripped them of their shirts, put then in handcuffs, and whipped them with electrical cables. Awad Sayidi, the local head of Gaddafi’s internal spy agency, the General Intelligence Office, had also arrived to oversee the interrogation. The Honorable Patriots were evidently viewed as an important threat.

Eventually, Belruin and the other prisoners were taken on a 15-hour ride to Tripoli in the back of a semi-truck, their hands cuffed behind their backs, forced to sit bent forward at the waist with their heads down. Any upwards glance would be met with a smack from a guard’s truncheon.

The truck arrived at an underground garage at an intelligence building in Tripoli, where interrogators once tried to force Belruin to sign a confession. When he refused, they whipped him with electrical cables again and put him in a cell with a man from the western port city of Misurata. According to Belruin, the interrogators had pulled out at least some of the man’s finger- and toe-nails. His hands were so swollen that Belruin had to feed him.

After two days, they put Belruin in a cell filled with several inches of water, making it impossible for him to lie down to sleep. For days, he spent much of his time in a crouch, leaning his back against the wall. After the fourth or fifth day, he began to hallucinate images of his dead father and his brother. Another interrogation followed.

They slapped Belruin when he refused to confess to the allegations, but he was given a ragged mattress to sleep on. During another interrogation, he was hung upside down by his knees, his hands stuck, cuffed behind his legs. They hit his feet with poles until they bled and became numb. At other times, they brought in a dog, which snarled and snapped at Belruin, tearing away some of his pants with its teeth.

After several years, during which Belruin was transferred to different places, including villas used by ad-hoc “people’s security” forces to house prisoners, he was placed in Abu Slim, a notorious Tripoli prison. It was there, he claims, that in 1988 Gaddafi himself arrived to bestow a symbolic amnesty on thousands of inmates. In a televised ceremony, Gaddafi, riding on a bulldozer, broke down one of Abu Slim’s walls. Benghazi residents say video exists of the act. The prisoners were told to leave without questioning and made to sign an oath declaring they would never again involve themselves in political activities.

Belruin never saw a judge or prosecutor, and his charges – if there were any – were never explained.

“We had no life until this revolution, we were oppressed people … the smallest freedom for the first time, we were nothing, we were a dead people, we didn’t have any rights,” he said.

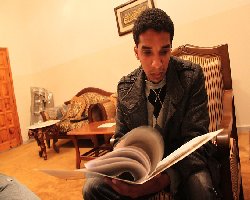

PHOTO CAPTION

Former criminal prosecutor Ayman Gheriani reads a classified internal security surveillance file

Source: Aljazeera.net

Home

Home Discover Islam

Discover Islam Quran Recitations

Quran Recitations Lectures

Lectures

Fatwa

Fatwa Articles

Articles Fiqh

Fiqh E-Books

E-Books Boys & Girls

Boys & Girls  Women

Women