More than a week after a section of the Moqattam hills cracked and fell on parts of Manshiyet Nasser, Cairo's largest shantytown, experts are warning of further landslides and potential disasters.

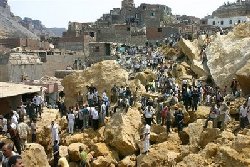

The rockslide, which government geologists estimated spanned an area 60m wide and 15m long, destroyed over 50 homes, killing 82 and leaving hundreds of people homeless on September 6.

Eight days after the tragedy, workers have only now started to dig tunnels in search of missing people feared dead beneath the rocks.

Aboul-Ela Amin Mohammed, the head of the earthquake department at the National Research Institute for Astronomy and Geophysics, said that the entire limestone plateau remains in danger of further collapse.

"It is not the first time or the last time this will happen," she told Al Jazeera.

"The area is full of densely-packed informal housing with no central sewer system. When the sewage touches the fragile surface of the limestone, it changes its consistency into a flour-like paste," she said.

Fear of collapse

Mohsen Abdel Mageed, 32, a garbage collector and resident of the shantytown, told Al Jazeera that there had been signs the hillside would collapse, but that these had been ignored by the authorities.

"It was just a matter of time until the rocks fell on our houses."

"We anticipated that a tragedy like this would happen. It happened in the past and we know it will happen again," he said.

In 1994, a rockslide in the same area killed 30 people, but without any affordable alternative housing, residents were forced to return.

Abdel Mageed's house was still standing after last week's rockslide, but he fears it could collapse at any moment and many of the residents of the densely populated area share similar concerns.

Now, panicked residents are living on the streets in makeshift lodging because they fear returning to what they believe to be a highly volatile terrain.

Oldest slum

Manshiyet Nasser is one of Cairo's oldest slums, established in the late 1960s in a wasteland between a centuries-old Islamic cemetery and the Moqattam plateau.

For years, the shantytown grew in the shadow of a limestone cliff.

As housing costs forced many Egyptians to become squatters, wooden shacks and shoddy brick apartments spread over the hill between unstable cliffs, heaps of garbage and an unused railroad track.

A UN Habitat report estimates that Manshiyet Nasser is now home to 1.2m people squeezed into five square km of narrow lanes and ramshackle apartments.

Though the apartment buildings clearly violated construction codes, residents unable to afford homes elsewhere bribed city authorities to allow them to stay.

But many in Manshiyet Nasser fault the government for a series of corrupt and inept policies which they say failed to protect the slum dwellers from a calamity that experts had long predicted.

Many of the residents from Manshiyet Nasser say they tried to warn the authorities of the Moqattam's imminent collapse.

Ashraf Bayoumi, 47, mechanic and father of three girls, lives in an apartment building that stands on the verge of collapse and complains about the cracks all over the walls of his apartment building.

"I went to the police station to ask to be relocated, but they said to only come back once my house falls down.

"They will only care about us once we die," he said.

Hani Abdel Moneam Riyad, 24, sells pens on the street of the shantytown for a living.

A father of five children, he was able to pull his wife and children out of their apartment building before it was sliced in half by the impact of the rockslide.

"I'd tell the policeman, come with me, I'll show you what we're dealing with, but he'd just sit there in his chair and wouldn't even look in my direction - as if I weren't there," he said.

"The police never do us any good," Riyad said.

Blame game

On September 14, an emergency session of parliament failed to reach any conclusions on how to deal with the situation or provide the dozens of homeless any quick reprieve.

Parliament members and government officials spent most of the session trading accusations of blame for the tragedy, local media reports said.

But the government says that its previous warnings of danger had been ignored by Manshiyet Nasser residents.

It maintains that residents refused to relocat into substitute apartments provided for them.

Residents deny snubbing the government's offer, saying they agreed to move, but extreme poverty forced people to live in shantytowns instead of paying unaffordable rents for the alternative dwellings.

Egypt's opposition groups, including the banned-but-tolerated Muslim Brotherhood, have singled out the government for blame, saying inept housing policies and corruption allowed the rockslide to happen.

The government has for its part promised housing for the displaced shantytown residents. A week after the rockslide, state media reported that only 112 of the residents from Manshiyet Nasser have been relocated.

Mourning continues

That comes as little comfort to those who have lost families in the rockslide or are clinging onto hope for word that those trapped under the rubble are still alive.

As relief efforts enter the ninth day, the bereaved wails of women could still be heard over the calls to sunset prayer, ending another day of fasting for the month of Ramadan.

Layla Kamel's husband has been trapped under the rubble for eight days.

The 56-year-old mother of three daughters prays that Ayman, her husband, found some way to stay alive.

In the first 24 hours after the rockslide, she was able to reach her husband by mobile phone.

"He kept saying he couldn't feel his legs, and talked about the weak condition his body was in."

"I want to help him but I have no idea where to locate him and the government forces have pushed every one - including family members - away from the site so they can clean up the rubble," she said.

Kamel says she has not heard from him since the day of the rockslide.

"It disturbs my heart to know he could be dead ... I can't stop shaking," she said.

PHOTO CAPTION

In this Sept. 6, 2008 file photo, Egyptians search for victims at site where a massive rock slide buried many dwellings at an Egyptian shanty town south of the capital Cairo, Egypt.

Source: Al Jazeera

Home

Home Discover Islam

Discover Islam Quran Recitations

Quran Recitations Lectures

Lectures

Fatwa

Fatwa Articles

Articles Fiqh

Fiqh E-Books

E-Books Boys & Girls

Boys & Girls  Articles

Articles